Other symptoms can include:

Headache (most common)

Dizziness

Tinnitus

Hearing loss

Blurred vision

Emotional Lability

Irritability

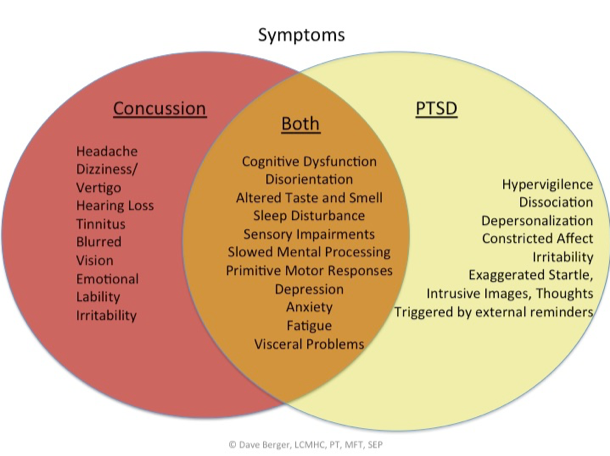

Additional symptoms can overlap with symptoms of PTSD:

Altered taste and smell

Sleep disturbances/insomnia

Fatigue

Sensory impairments

Attention and concentration deficits

Slowed mental processing (slowed reaction and information processing time)

Memory impairment (mostly recent memory)

Depression

Anxiety

The suffering from minor traumatic brain injury is significant. The immediate treatment should be rest; just as a broken bone is rested and immobilized for a period of time, the brain needs rest. A minimum recommended rest time is a week and includes REST—no reading, school, work, television, cooking, sports, etc. Gentle, relaxing music and easy, short walks can be OK, but rest, rest, and more rest is necessary. Medical consultation is a must.

If your client has had one or two experiences of concussive injuries and you are lucky enough to work with them within a couple of weeks of the injury problems can be avoided. If your client has had multiple concussions or long-standing symptoms treatment can help but will take a good deal longer—6-12 months at least. Some symptoms from the excessive neuronal damage and subsequent inflammation may not change. The shock trauma to the brain, meninges and skull can change.

Somatic Experiencing® for the boundary breach and impact injuries and BASE™ Bodywork oriented toward the physical and autonomic shock in the bone, meninges (membranes) and brain structure can make significant differences in symptoms of minor traumatic brain injury or concussions. Only nature and a healthy lifestyle can help the results of the destruction caused by the torn neurons.

Rest, grounding and supporting the parasympathetic nervous system can be very helpful in the acute stages. After the first couple of weeks, and if the initial symptoms have decreased or dissipated you will want to address the high impact injuries—the elbow to the head, the soccer ball hit, the dashboard that came up to quickly during the car accident, the sound blast or the fist to the face. Go slowly and gently, though, because there will still be a level of fragility. A client may feel moments of pain experiencing the implicit recall of the injury to the head, but it should resolve quickly, and s/he will feel better.

Working with the internal impacts is also necessary and will often emerge while working with the external impact. To the client it might feel like a sharp pain, dull ache or flash of light at and through the vectors of internal impact. It is vital to support a slow approach to the impact and boundary rupture—people like to rush through the story. Who wants to feel it again?!

Working with someone who has had a concussion has several stages. Always paying attention to capacity and manageability of activation, the practitioner, working within their scope of practice and training, is guided by a client’s symptoms, especially his or her ability to handle settling down, deactivation and discharge (going more parasympathetic) as well as the ability to handle increases in sensation in the head—skull and brain. Too much parasympathetic dominance can set off a chain reaction toward dissociation while too much physical sensation in the head can trigger pain and shock. Both of these ‘directions’ will expand as a client gets better, but work needs to be gradual, perhaps more gradual than other physical injuries and impact experiences because they can trigger symptoms of PTSD—anxiety, disorientation, sensations of falling, being hit, recall of a high impact event, pain and the initial or subsequent symptoms. If the event or events included other people relational trauma can emerge. If medical intervention was needed and traumatizing that will need to be de-coupled from the concussion injury.

As you can see, there is overlap with in symptoms between MTBI and PTSD. One can trigger the other and, together 1+1 can equal well more than 2: they potentiate one another. It’s like the lowest note on an upright base in the orchestra, when played for a long count, it can stir strings in other instruments nearby. This is resonance. When two bases play the same note, they will accentuate the sound and, boom, you have a huge vibration. If this is someone’s cranium, ouch! It can hurt, cause vertigo, pressure, dissociation, memories, images, unpleasant emotions, etc. Dealt with in the smallest of increments, though, the symptoms will ease and mitigate. This is how they disengage from one another and allow for a degree of self-regulation to re-form.

Just as the most acute phases of a concussion require significant rest and healing time for the brain, time after a session, especially sessions in which a client begins to feel the healthy, gentle movement of their brain inside their skull, requires a significant amount of rest afterward. A couple of days of no activity is a minimum. It can feel oddly good yet disorienting to feel one’s brain floating around in their skull after a period of time of structural immobility from a concussive impact.

Bodywork is an essential component in the treatment for MTBI. It needs to have a special degree of specificity and sensitivity in order to locate the region and structures of the brain, meninges and skull that are in shock. A practitioner’s focus is to Meet, Greet, Listen and Receive. Let your hands meet your client. Greet the structures you are touching. Listen with your hands for flow, ease and vitality, and for brittleness, dis-ease, lack of flow, sluggishness. Structures you will be ‘listening’ for with your hands include the skin/scalp, fascia, bone, fascial layers of meninges, brain and specific parts of the brain. You might feel a magnetic pull or as though one part of the brain is like a partially deflated balloon; It might feel like the saran wrap is too tight in some areas, or like one area of the skull and brain are glued together. As you listen and receive these parts they will begin to ‘wake up’ and more flow or ease will evolve.

Bodywork is not limited to the cranium just as a sitting psychotherapy model of SE is not limited to the moments of impact. Other parts of the body need to be addressed to open survival energy exit routes such as the arms and legs. Often, it is best to work areas of the body geographically distant from the cranium in order to establish or re-establish a flow of tissue structure first. Kidneys, visceral fascia and organs, joints can typically be involved with shock, shut down and constriction and should be listened to and worked with also.

Occipital cradling in which the practitioner holds a client’s occiput and neck can free up structures used for orienting. Subtle preparatory movements of head turning can begin. This can be a good time to ask a bit about the blow to the head and track other movements and sensations that support a healthy completion to the threat response cycle.

While there is not a specific step-by-step protocol to working, things to consider are: the order of how to address the various levels of shock and tonic immobility a client has; the number and severity of his or her concussive history; present symptoms of PTSD and Post Concussive Syndrome a client is experiencing. The more general fear shock (deer in the headlight sympathetic charge) is often the most accessible and manageable. This is often seen while working with the Boundary rupture and repair. Brace, Let down, Rebound (more typically language in SE™ as Brace, Collapse, Rebound but Collapse is often misinterpreted) is a sequence often seen with working through a high impact injury. The bracing is a frozen flight or fight response from and against impact. Letting down as part of deactivation, discharge and settling allows for a relaxation into parasympathetic. Rebound suggests that stored survival energy is more available to the person.

Remember, the continuum of sitting SE and touch work of BASE™ is a vital continuum of treatment to offer either from one practitioner or practitioners working as a team.

There is a paradox of letting down toward a parasympathetic state when someone has been concussed as it can trigger symptoms of PTSD including feelings of helplessness, feeling out of control and of terror. The work needs to be navigated very cautiously and slowly and only after a client has some capacity to relax without symptoms. These can often be bypassed when a client is ‘put’ right onto a table for bodywork. This is why sitting up before lying a client on a table is an important consideration. Relaxing on a table can trigger helplessness as though one has gotten knocked out again, but it is often over-ridden when one is expecting bodywork. If a client experienced a period of unconsciousness from a concussion an implicit memory of a near-death state can emerge.

It is common that concussive injuries involve multi-directional forces. Any movement transition can trigger vertigo, a common symptom of concussions. The ability to transition positions, even the tilt of a head, needs to be built slowly. In other words, the window of resilience between sympathetic charge and parasympathetic charge starts out in a very narrow range of tolerance. Both sides of this autonomic continuum will gradually stretch, and the windows will widen. Depending on the degree of head trauma, concussive and PTSD symptoms the widening of the window can take from a single treatment to a year or more of regularly scheduled treatment sessions. This also has to do with how many concussive injuries and other trauma experiences someone has had.

If a concussion is the result of relational trauma or results in relational trauma, an added dimension may drive the autonomic nervous system dysregulation and needs to be addressed. Clarity of thinking and perception is important in decision making so uncoupling these ‘assaults’ is required but working with the concussion is imperative at first. Working with relational trauma might have to wait a bit until some level of clear thinking is available.

Another aspect of treatment includes education. Educating clients/patients about what a concussion is, why it is hard to diagnose, how it overlaps with PTSD and how to talk with educators, employers, colleagues, friends, and relatives supports a client’s healing process by allowing them the needed time to rest and recover.

What aspects of a concussion can we, as trauma therapists not help? This is an important consideration. The micro-tears from shearing and ripping of neurons result in the release a cascade of biochemical changes and local damage. BASE™ nor SE™ can effectively change these, but the autonomic and structural re-regulation from these works can be very effective at easing many symptoms and, theoretically, supports new neural growth.

The greater the degree of change and inflammation, the greater the symptomatology. We are hearing more and more about this from the military and in the professional sports arena, particularly the NFL, but it is not limited to sports or adults. Children, adolescents, and non-athlete adults can suffer the same way with repeated concussions. All contact sports (where the head can contact another hard object, not just another person) can result in a minor traumatic brain injury or multiple ones.

One last consideration. In addition to BASE™ and SE™ practitioners, other team members to consider are a neurologist, speech therapist, occupational therapist, physical therapist, and dietitian. The combination of concussion and PTSD is complex and requires several modalities for treatment.

Case Presentations

Case (Fred)—chronic, long term, multiple concussions

Fred is a 63-year-old Caucasian disabled truck driver who has a long history of concussive injuries, relational trauma, and medical trauma. He came to me about two years after his last and most devastating concussion. He was unloading his dump truck when the truck tipped over and he was thrown around in the cab of the truck striking his head on various parts of the cab. He recalls being unconscious for a short time, but his greatest recollection is the feeling of falling and being out of control.

Fred’s symptoms included severe and continuous headaches primarily on the left and right sides of his head “like a vice gripping my head”, nightmares, hopelessness, fatigue and “just never feeling right.” He relies on physical contact with his very supportive wife to help him calm down when he is agitated and in fear.

Treatment for Fred initially included one very brief ‘review’ of the accident to determine his ability to feel anything other than pain, his recall and to gather information. Following this, the focus has been twofold: first to establish an ability to relax and ground himself a little bit. Using Voo sound has been extremely effective for this. Adding to Voo we have used imagery, physical support at his shoulders while sitting and using implicit memories of various aromas and colors he likes. He has gradually developed an ability to relax and his headaches have decreased in intensity and frequency about 50%.

Since he treats his own headaches by exaggerating the vice grip by pressing the sides of his head inward, I offered to do the same while he was sitting up. This also gave me the opportunity to begin Meeting, Greeting, Listening and Receiving structures in his cranium. I gradually eased the pressure. With the support of my hands in this first bodywork session he did go into a very high sympathetic activation and bracing, then rapidly dropped his head with a terror of falling. Everything in his skull and his skull itself, felt like stone so I wasn’t surprised by this rapid autonomic change. We worked him through this, and he was able to relax a bit more. I sent him home that day with instructions to rest, rest, and rest. At the next session, he told me that he felt unstable and ‘like in the office here’ for 3 days and then his headaches starting lessening in intensity from their initial level. Since that session, they have also changed from continuous to intermittent and throbbing.

This session and the length of time it took for the change to happen isn’t to be concerning. It laid the groundwork for the next session in which a twitch of his eyes and head emerged when I asked him to ‘just’ recall an overview of the accident while sitting up. For the first time, he could feel the implicit memory of movement. The ‘twitch’ was the precursor to a flight response which, when asked, he described as ‘getting out of the way of the window.”

Subsequent sessions have been both verbal SE and BASE™ touch work oriented toward both affective and behavioral relaxation and reducing the structural immobility of his scalp, superficial fascia and the cranial bones. Orienting to present moments in the office keep him focused and interrupt his inclination of worrying about future pain (even 30 seconds into the future). Future sessions will start to address deeper structures of his cranium and working more directly with the boundary rupture and impact injuries and on his balance and equilibrium, grounding and core (physical and emotional) strength. He has not yet developed the ability to self-regulate effectively enough to start working with the accident itself in a more detailed way.

Because Fred has had many concussions over the course of 45 years his progress will be slow, and treatment will be in phases as he becomes more resilient. His improvement over these 10 sessions is evident in that his ability to fall asleep, while still not perfect, is improving, he has started driving again and he has spent full days at public events. None of this was possible before treatment started.

Case (Beth)—acute, one concussion

At 16 years old Beth headed a ball in soccer with perfect technique and, unfortunately, a poor outcome. After heading the ball, she was fine for a few minutes. The moment she came to the sidelines for rest she became dizzy and foggy, “weak in the knees”. This was her first (and hopefully last) concussion.

I saw Beth two weeks after her injury. She was put on a schedule of rest initially but was cleared to go back to school after only about 3 days. “I never really feel like myself, I still feel out of it and I have no interest in playing soccer.” These and fatigue were her primary complaints. Her parents described her the same way.

I asked Beth to tell me what happened and as she described how she headed the ball I observed her pull her head and neck back but never thrust her body forward into the ball like a soccer player does. This lack of movement suggested to me that that was the moment of impact, but she was coherent, had good inflection and prosody in her voice, and clear so I let her continue with the story. When she was done, I asked her to tell it to me again slowly and to feel the story her body was telling her at the same time. With feedback she noticed how she hesitated at the moment I described above so I paused her. As she turned her head ever-so slightly I asked her if she was turning her head toward the right or away from the left. She felt-thought a moment while in the freeze, “toward the right so I could head the ball with the left side of the front of my head.” Another clue as to what happened and how we might have to progress. I gave her time here to settle and relax. The first segment of work was done. “That was weird,” she said describing how she didn’t even realize that she chose to do this on the field. “I just did it.” This is a perfect example of the nature of implicit memory, non-conscious motor function choice under high-pressure situations—reflexive, instinctual movement.

Next, I had Beth lie on the table and cradled her occiput, neck and upper thoracic spine (she’s short). As she settled into my hands as best she could while still somewhat braced, I asked her again to tell me what happened. This time I could also feel her braced musculature begin to soften and the orienting toward the right begin. I supported the movement which, at first, she did not feel. “Ouch, that was weird.” She described a sharp pain on the left of her forehead followed by “something inside my head”. It was brief and I continued to support both the relaxation and movement of her head and neck while also Listening with my hands to her cranium which began to soften and flow. Again, she said, “that is totally weird (only in the words of a 16-year-old)” describing how she could feel her brain move around gently inside her skull. I, too, could feel flow inside her skull. This is the floating movement inherent in our craniosacral system when it is balanced. I had her rest on the table and enjoy the sensation. There was a brief shutter from the top of her head down her trunk—autonomic discharge. After this I invited her to slowly come to sitting.

I educated her and her father about the importance of resting for the next 24 hours. She was symptom free after this.

These, obviously, are two extremely different presentations and trauma treatments for concussions, yet they represent the huge continuum of concussive injuries.

References

1. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012.

2. Giza & Hovda, 2001, J Athletic Training